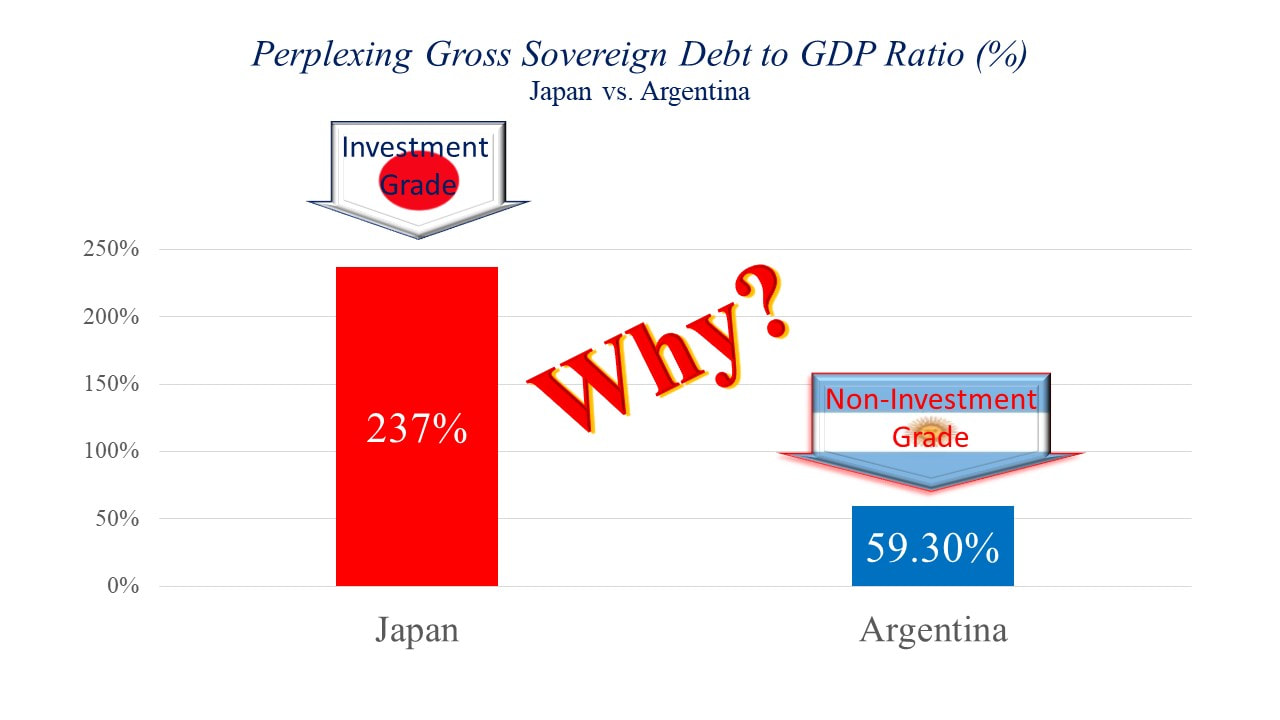

Perplexing Sovereign Debt to GDP Ratio:

Between 237% (2017) Japan and 59% (2018) Argentina,

which is more Risky?

Published: 25 October, 2018

Last Edited: 3 January, 2022

by Michio Suginoo

INTRODUCTION

|

Today, Japan is far more indebted than Argentina.

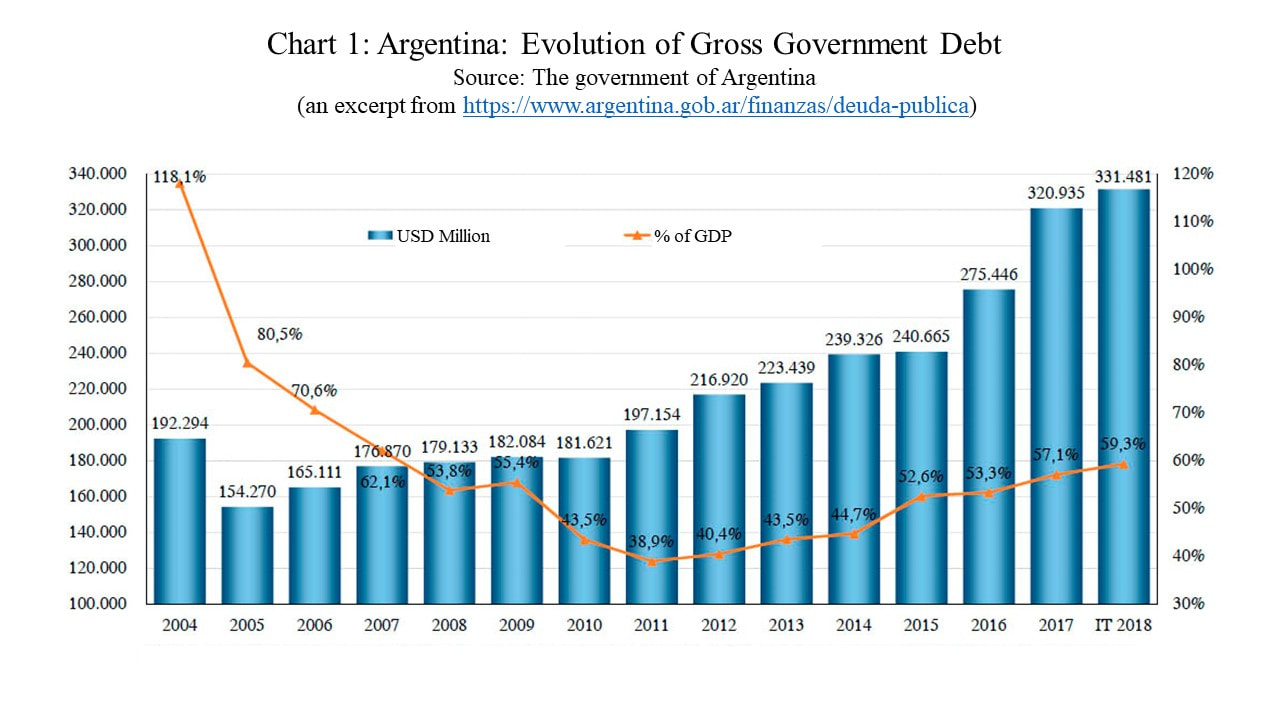

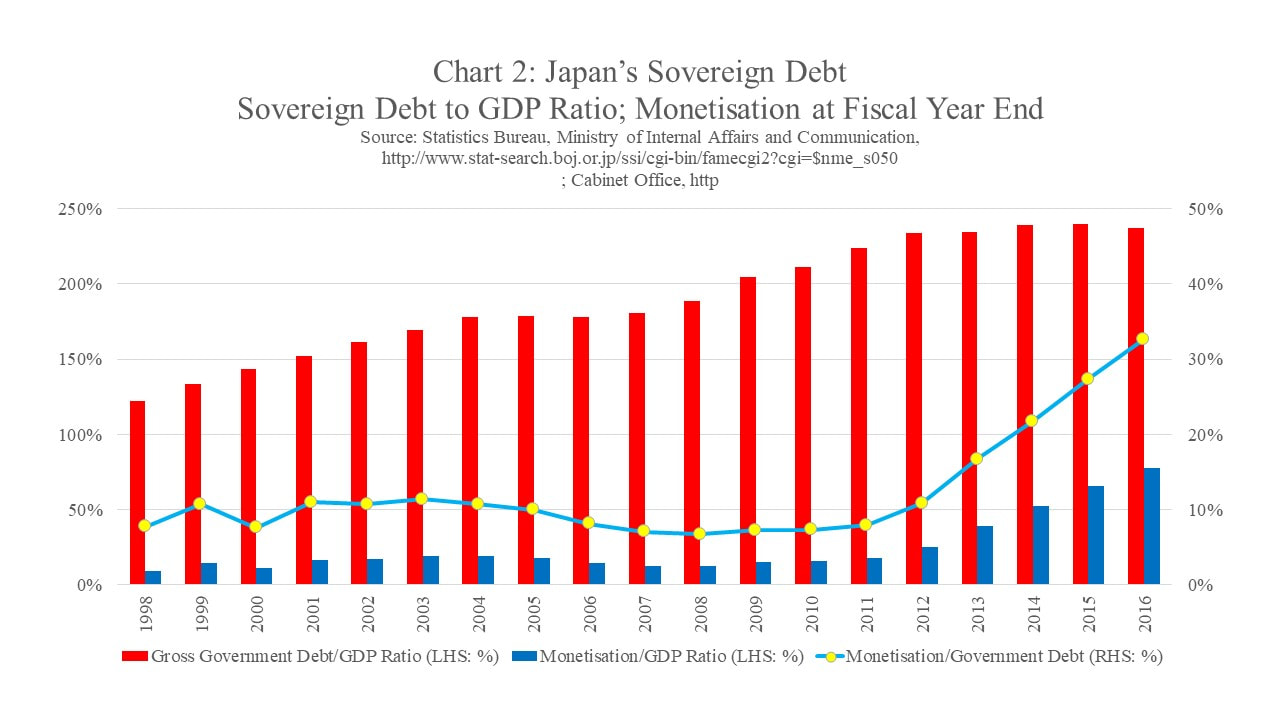

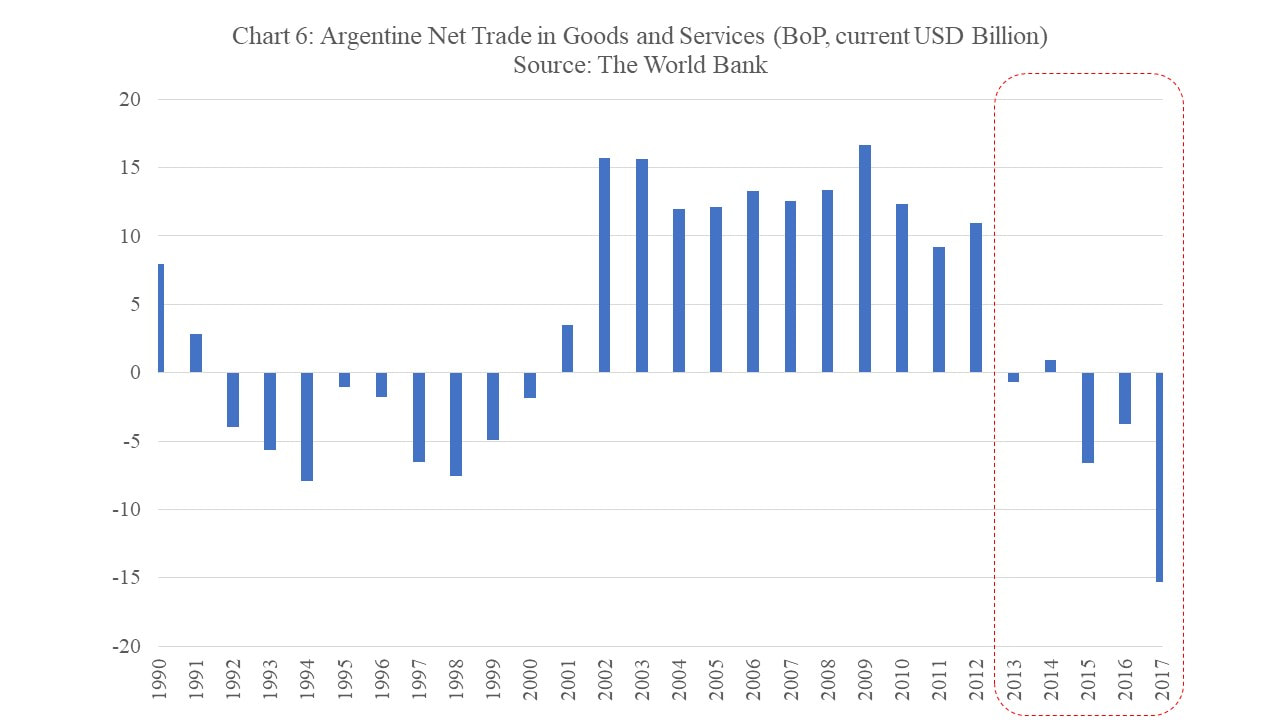

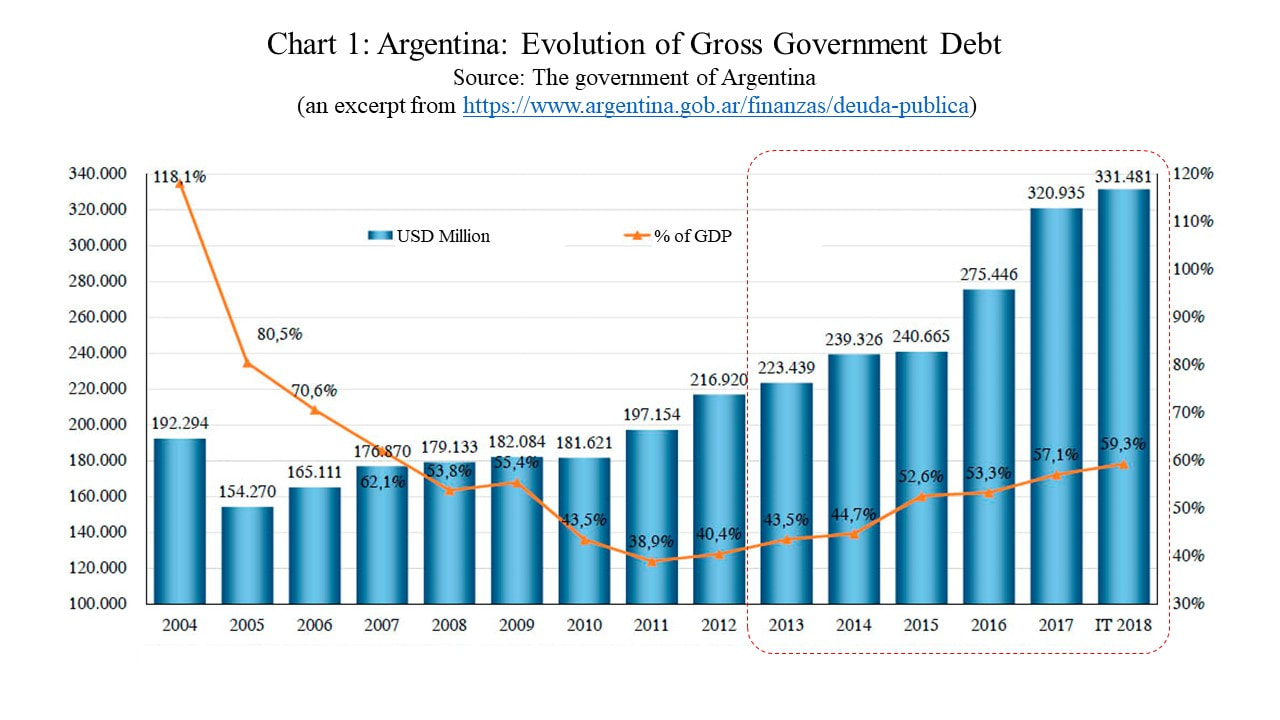

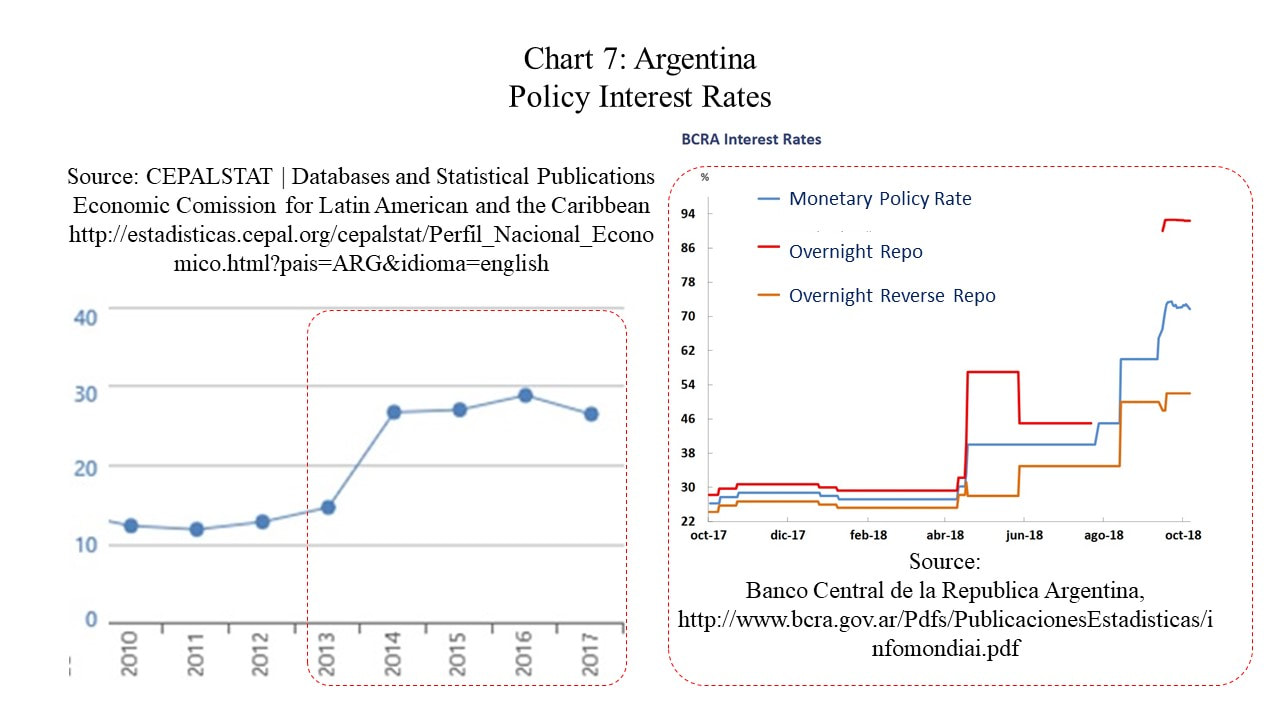

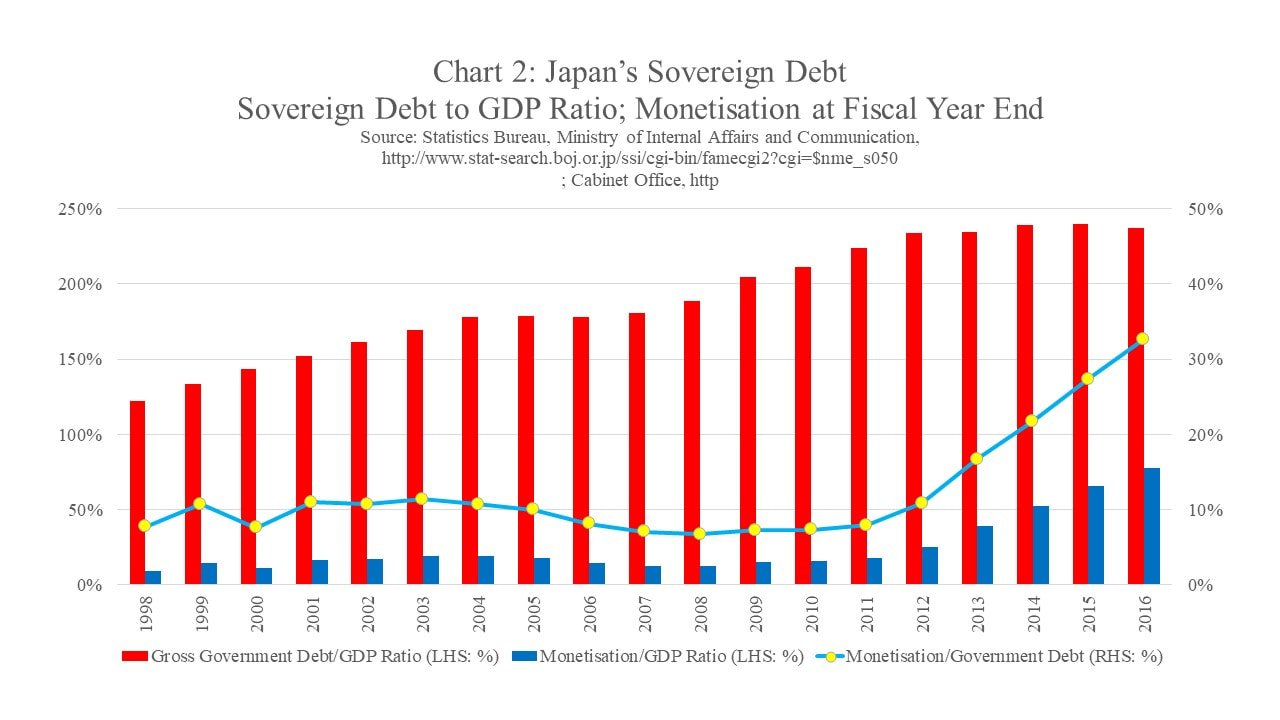

‘Gross Sovereign Debt to GDP ratio (Gross SD/GDP Ratio)’ is a measure to compare the level of sovereign government debts among different peers. In this measure, Japan has the world top position of 237% as of April 2017 (Chart 2); and Argentina has 56% in 2018 (Chart 1). If the government debt to GDP ratio is a metric to measure the credibility of a government’s fiscal and monetary management, Japan.gov must be far less credible than Argentina.gov. On the other hand, the credit ratings of their sovereign bonds cast a totally different story. While Japan’s government bonds (JGB) possesses an investment grade rating—rated A1 by Moody’s (December, 2014), A+ by S&P (April, 2018), and A by Fitch (April, 2017)—Argentina’s government bond (AGB) has a speculative/non-investment grade rating—rated B2 by Moody’s (November, 2018), B+ by S&P (August, 2018), and B by Fitch (May, 2018). The more you borrowed, the better credit rating you get. Isn’t it perplexing? If you are not perplexed, here are two very natural questions:

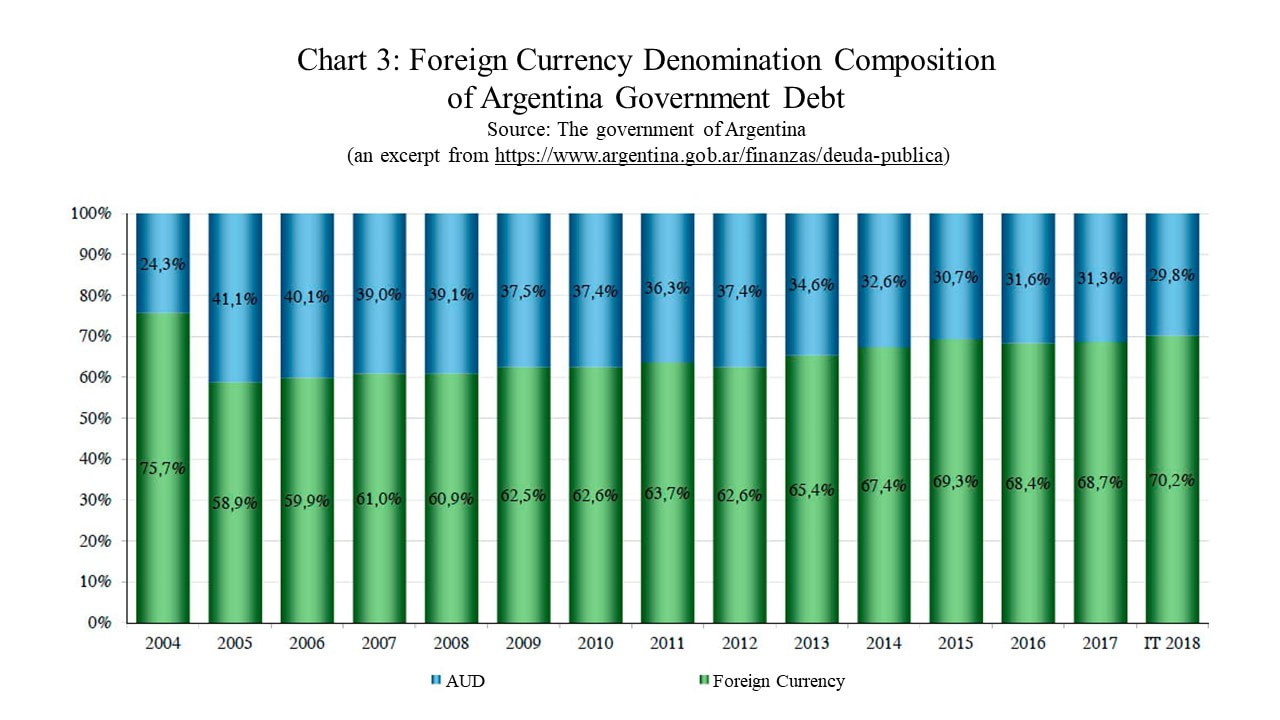

Simply put, this counter-intuitive relationship between ‘Gross SD/GDP Ratio (Sovereign Debt to GDP Ratio)’ and ‘credit rating’ is shaped primarily, if not only, by the difference in the proportion of foreign-currency denominated external debts between these two countries. On one hand, most of, if not all, JGBs (Japan’s Government Bonds) are denominated in its own local currency, JPY (Japanese Yen). On the other, a significant portion of AGB (Argentine government bonds) are denominated in foreign currencies, predominantly in USD (Chart 3). This difference becomes critical for Argentina at times of the maturities of existing debts (the repayment of existing debts to their creditors). Argentina has to earn USD in order to repay its USD-denominated external debts. That would deprive Argentina of its sovereign independence over fiscal and monetary policies. This content focuses on this primary driver, the denomination of sovereign external debts, that divides the fate of sovereign debts between these two countries. Here, in order to put them into a perspective of credit rating, let’s contemplate a stress test situation to examine their insolvency risk. Now, we assume a crisis situation under the following two assumptions:

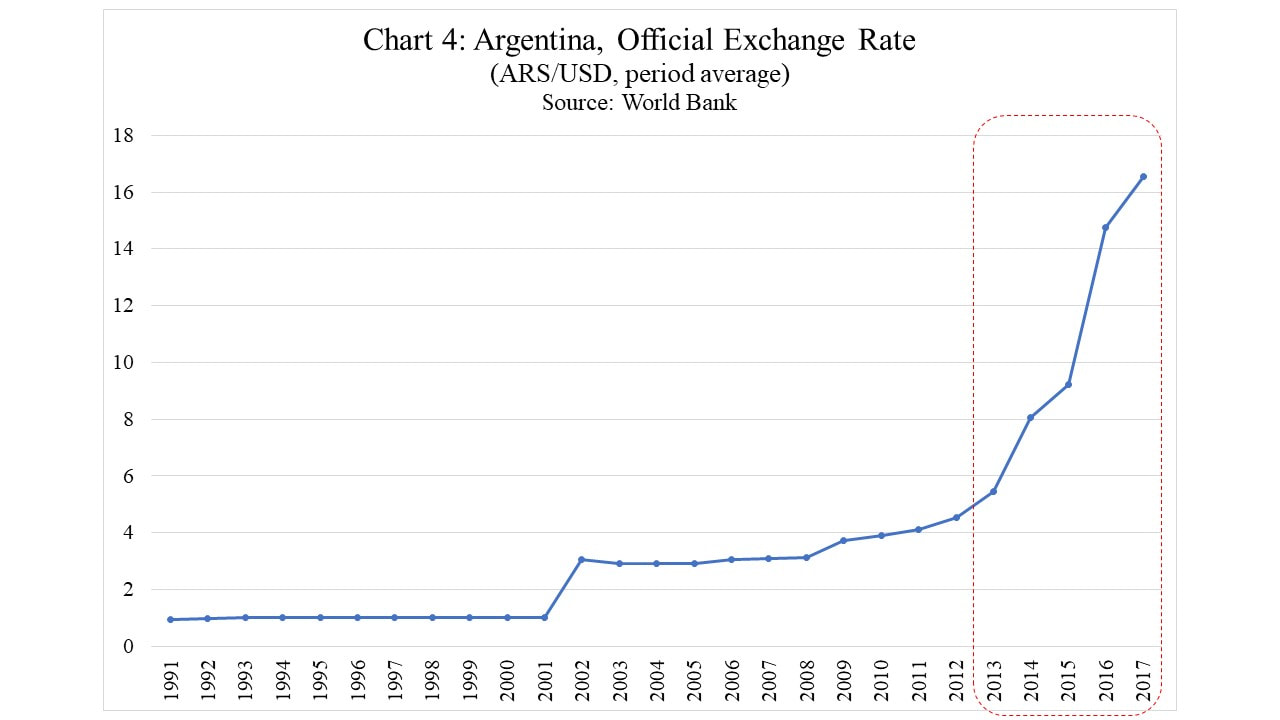

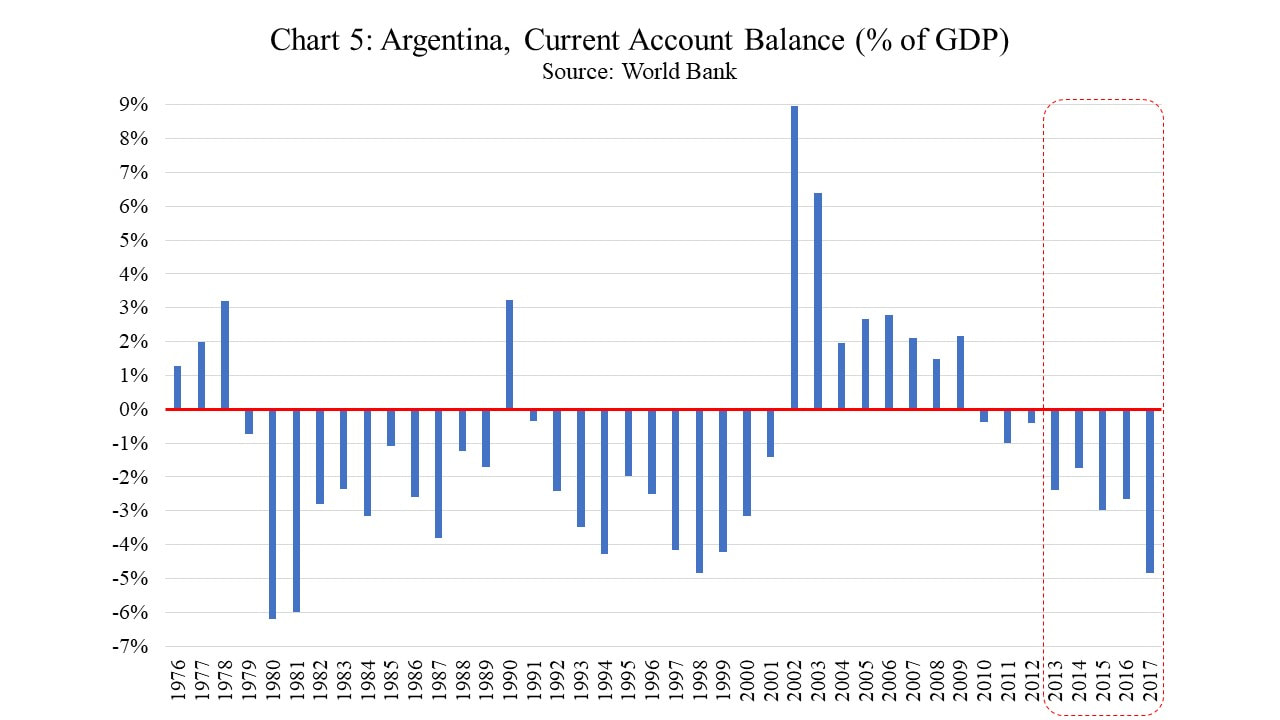

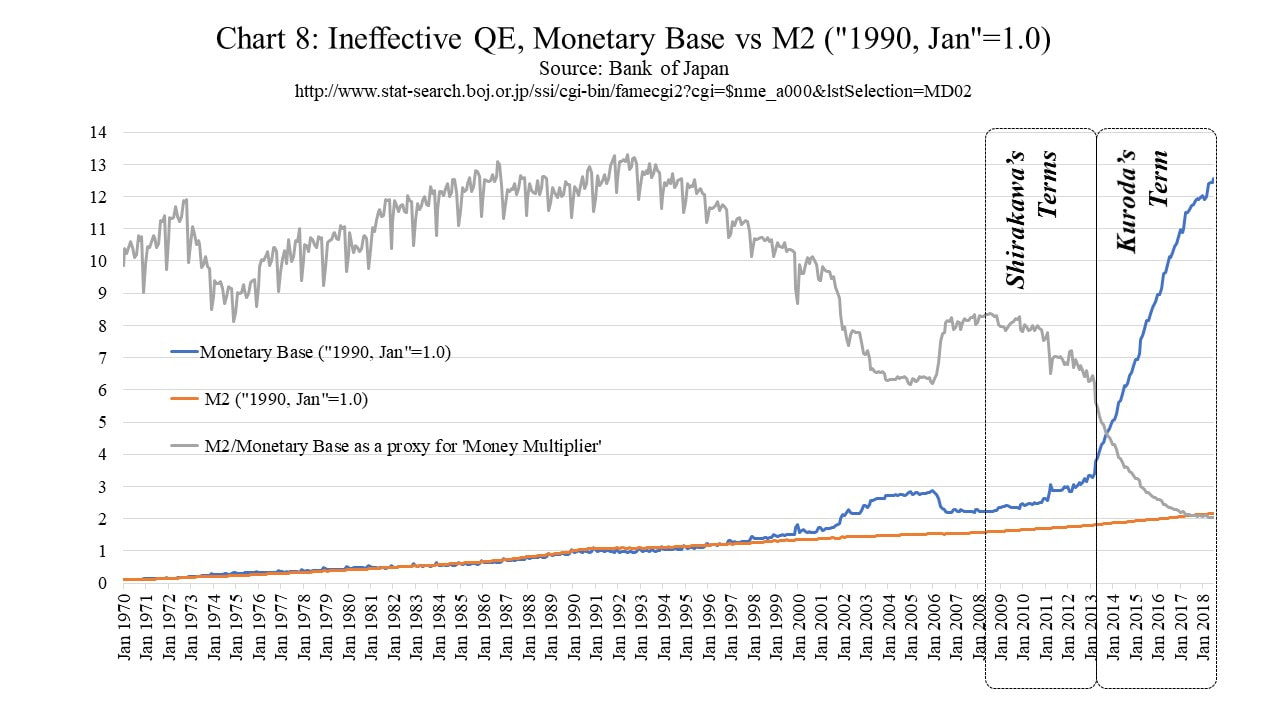

As of today for Japan— whether it works forever is a different question to be discussed later — it is a matter of issuing its own currency to service its outstanding sovereign debt, simply because its debts are denominated in its own currency. This is called ‘monetization’ of sovereign debt. The monetized portion of its debt does not necessarily need to be repaid (to be explained later). Thus, it is not a compulsory liability in a strict sense. In this sense, Japan appears to have no insolvency risk. Is that so simple? Can Japan increase its debt indefinitely through monetization? This would be discussed later. On the other, given the same crisis conditions, Argentina, in order to pay back the portion of its USD denominated external debts, needs to earn USD. In other words, if Argentinian currency (ARS) depreciates materially, the local currency value of the Argentinian external debts explodes. Thus, for the case of Argentina, the sovereign debt management would involve currency risk: solvency risk and currency risk become the two sides of the same coin in Argentine sovereign debt management. For the case of Japan, currency risk has no material involvement in the repayment process of sovereign debt: since the portion of foreign currency denominated external debts is small. This difference in the proportion of foreign-currency denominated external debts can result in a critical difference in solvency dynamics. Despite the fact that this difference is not the only factor that differentiates these two countries, it is a critical difference that divides the fates of these two countries in the architecture of their sovereign debt management. Keeping this notion in mind, let’s compare the economic dynamics of these two countries’ sovereign debt management, one by one. Now, we start with Argentina. ArgentinaRepeatedly, our question is: while Japan’s government’s ‘Gross Sovereign Debt to GDP Ratio’ (SD/GDP Ratio) is more than double Argentina’s one (Chart 1), why would Japan deserve a better credit rating than Argentina?

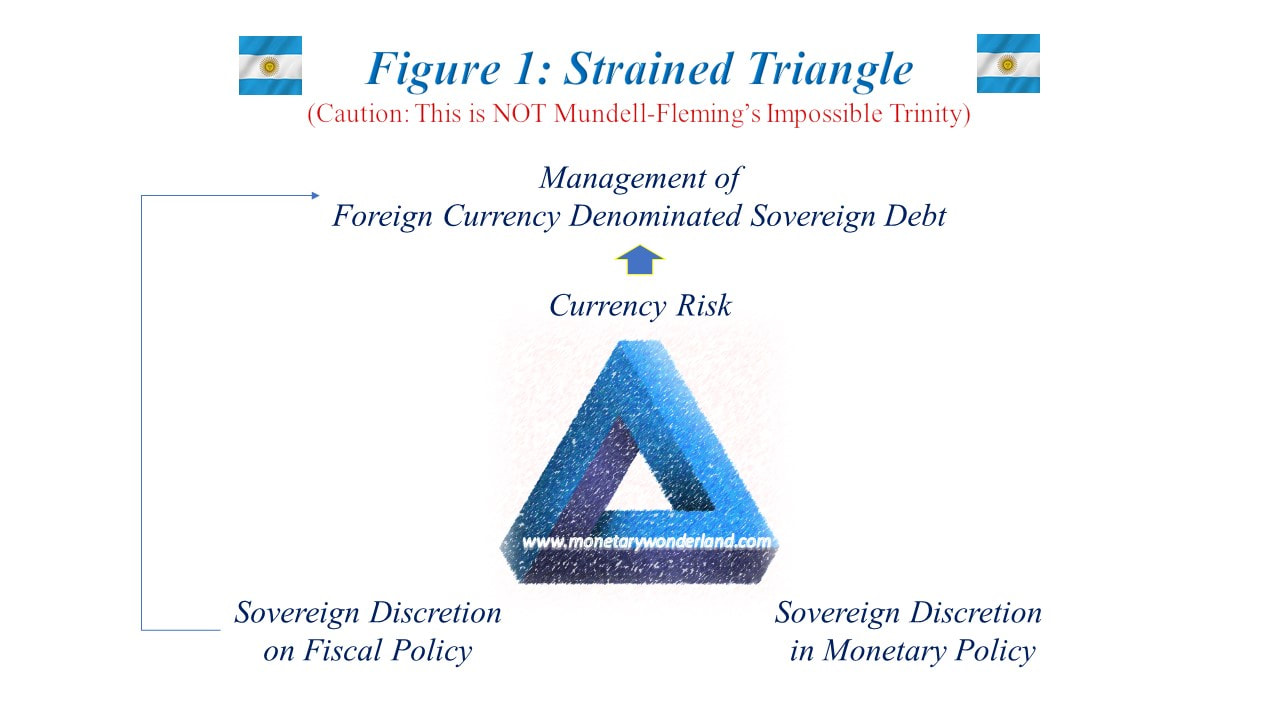

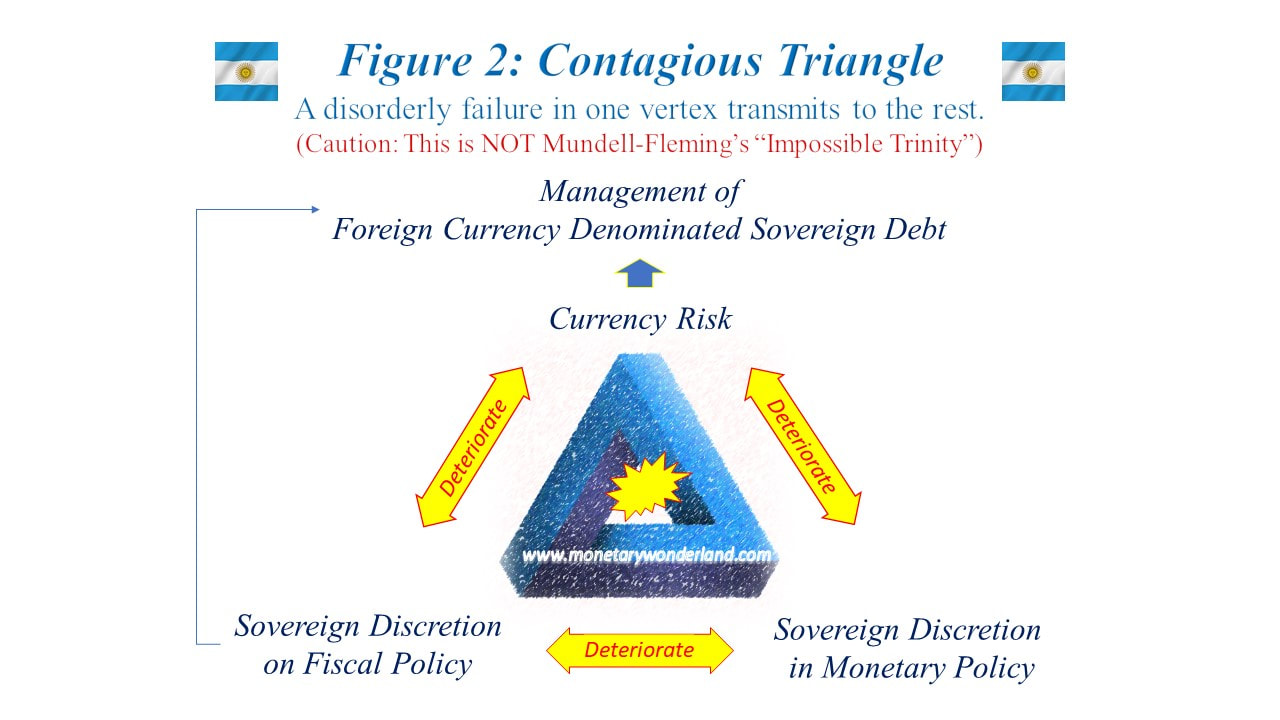

As stated earlier, a significant portion, around 70 %, of AGB (Argentine’s government bonds) is denominated in foreign currencies (Chart 3), predominantly in USD. That exposes Argentine sovereign debt management materially to currency exchange risk. As a result, the government of Argentina has an intense political priority on currency stability — although they fail. That deprives Argentina of its sovereign independence over fiscal and monetary policies, by imposing on the country extra constraints that Japan does not face. Although there might be multiple ways to slice the unfavorable dynamics, I would like to portray it in a framework of the ‘Strained Triangle’ illustrated in Figure 1: the presence of foreign-currency denominated sovereign debts constrains three objectives: sovereign debt management; full sovereign discretion in fiscal policy; and full sovereign discretion in monetary policy. (Caution: This is different from the famous ‘Mundell-Fleming Impossible Trinity.’)

|