Enter the Monetary Wonderland

Part 2:

Cycle of Paradox

Published: 30 August, 2018

Last Edited: 16 September, 2018

by Michio Suginoo

INTRODUCTION

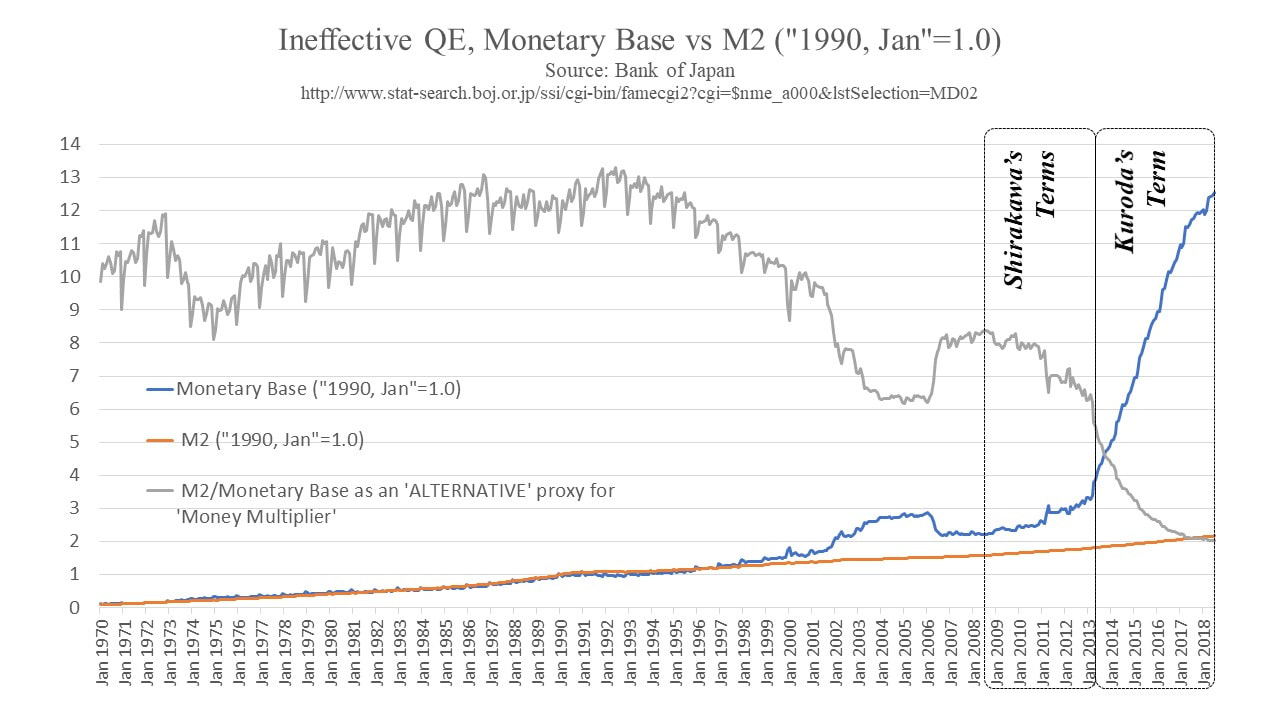

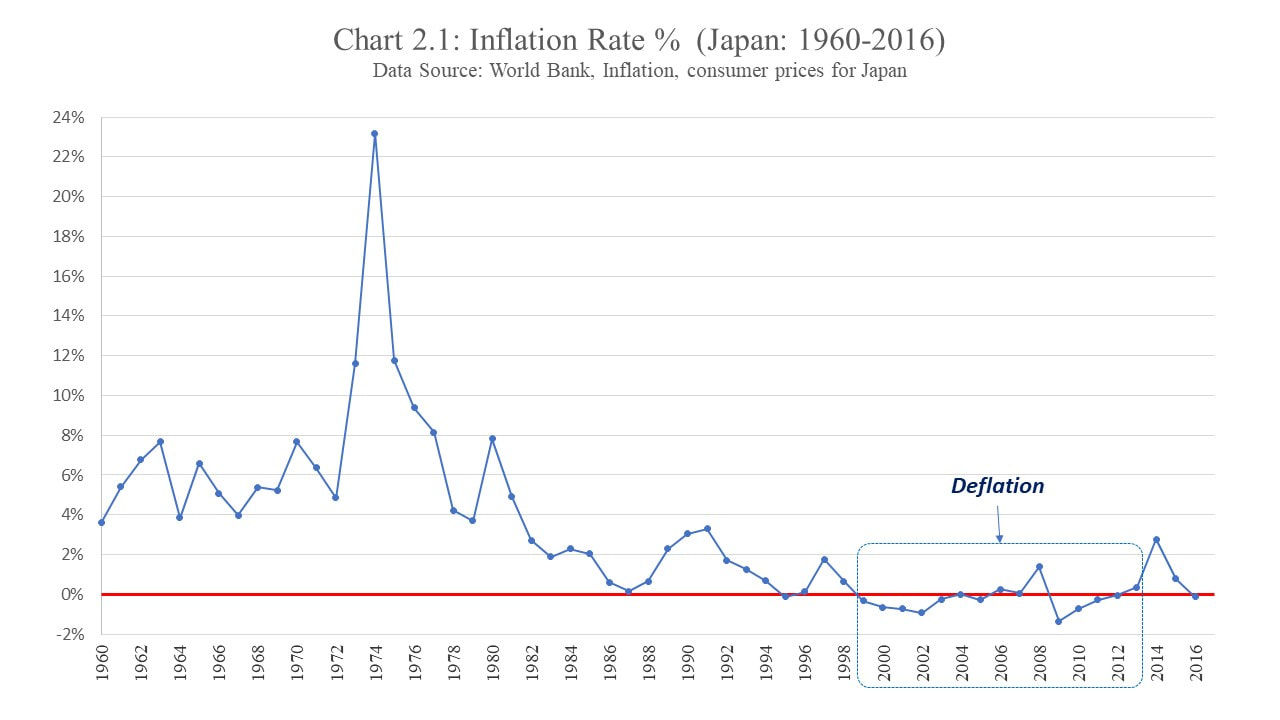

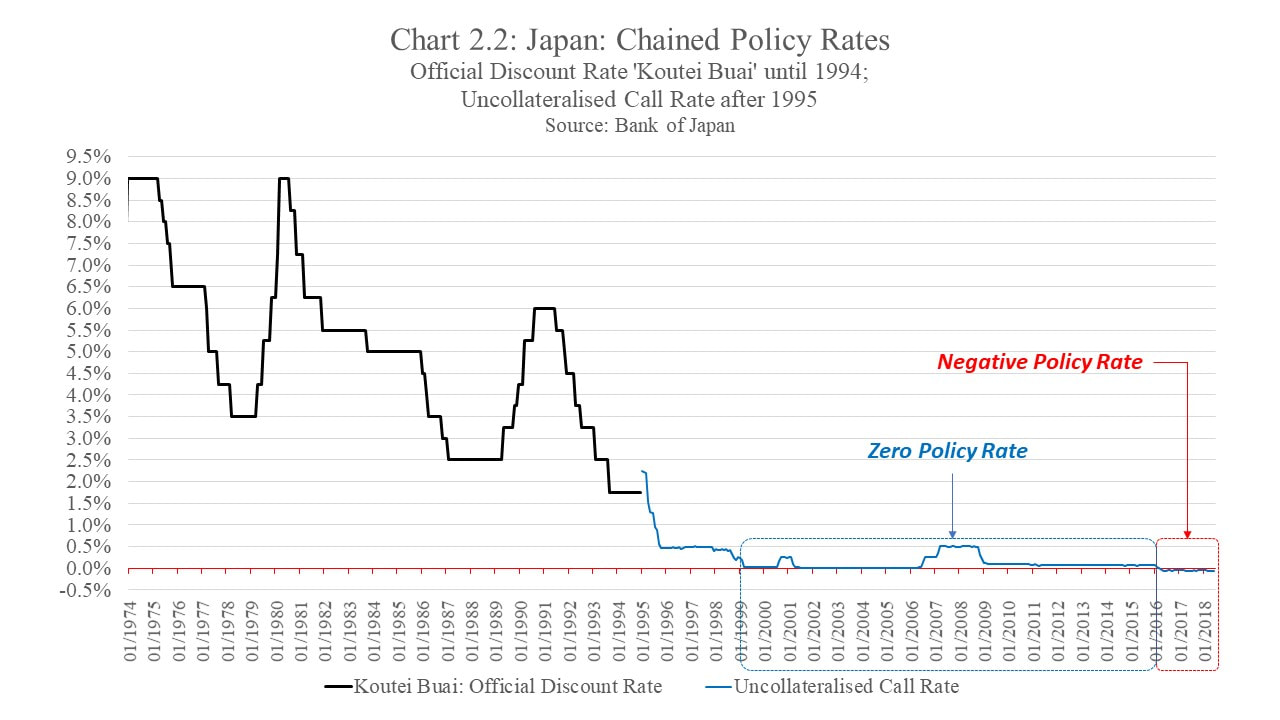

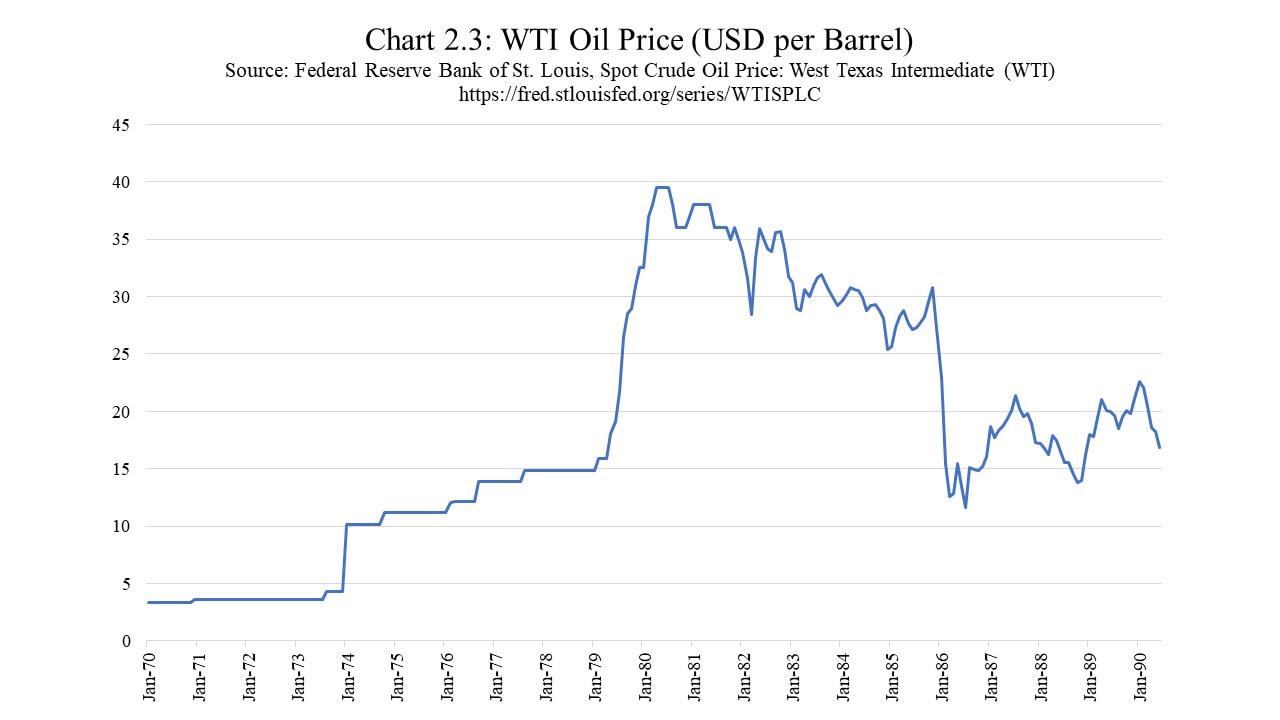

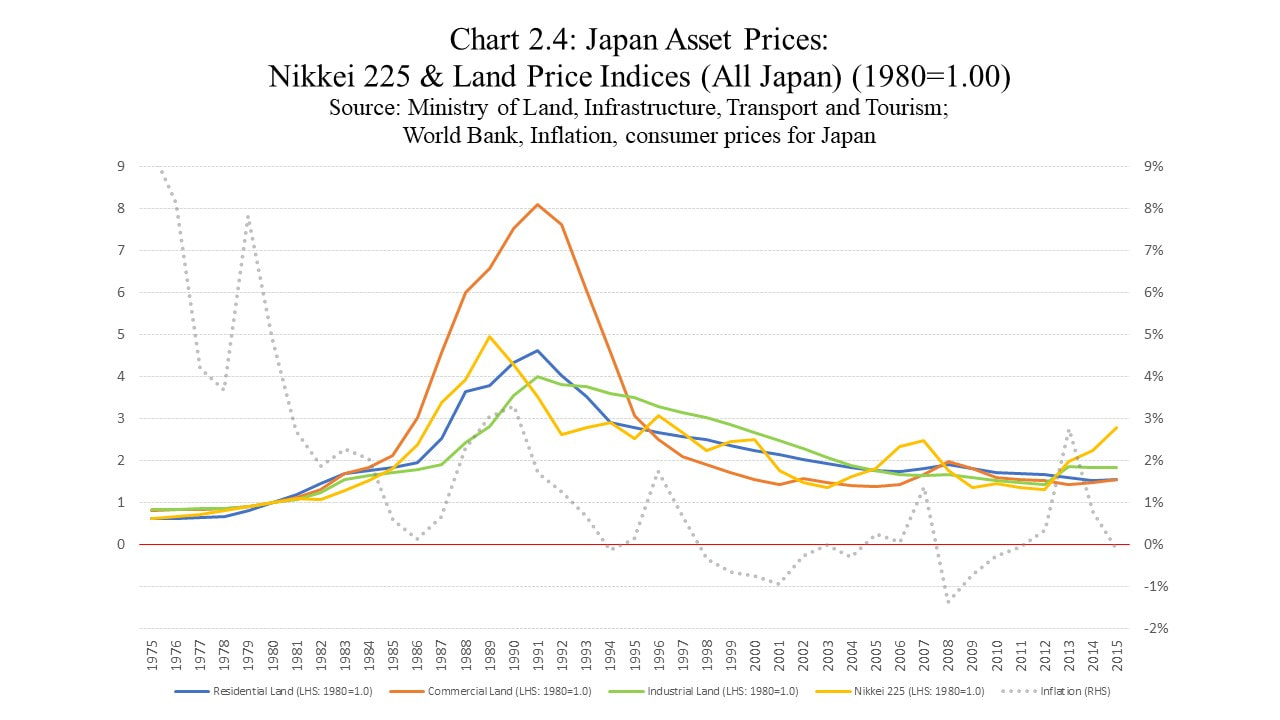

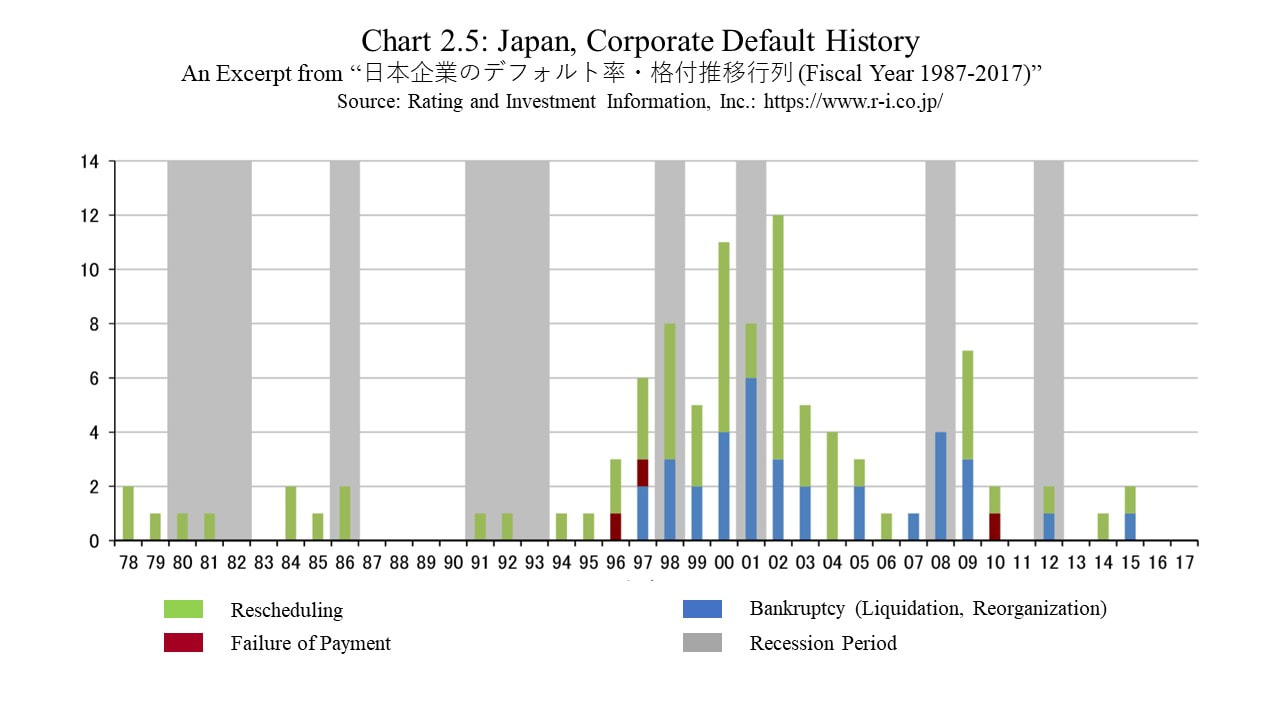

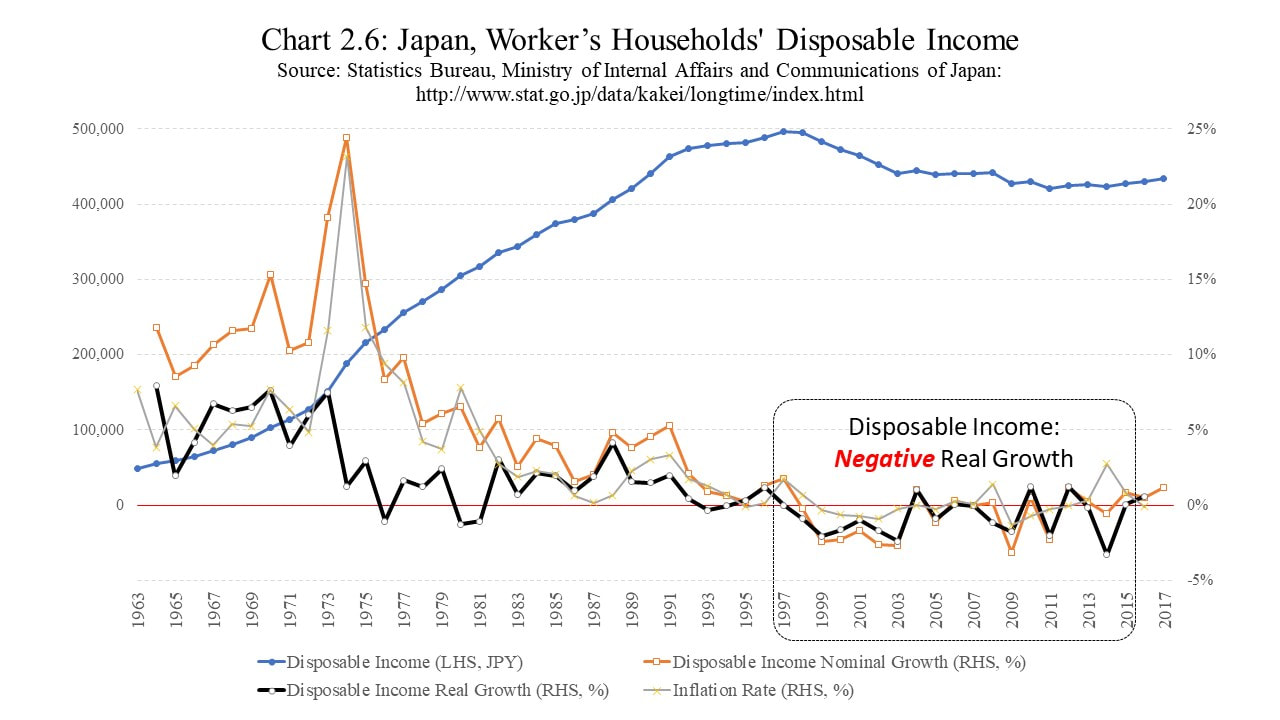

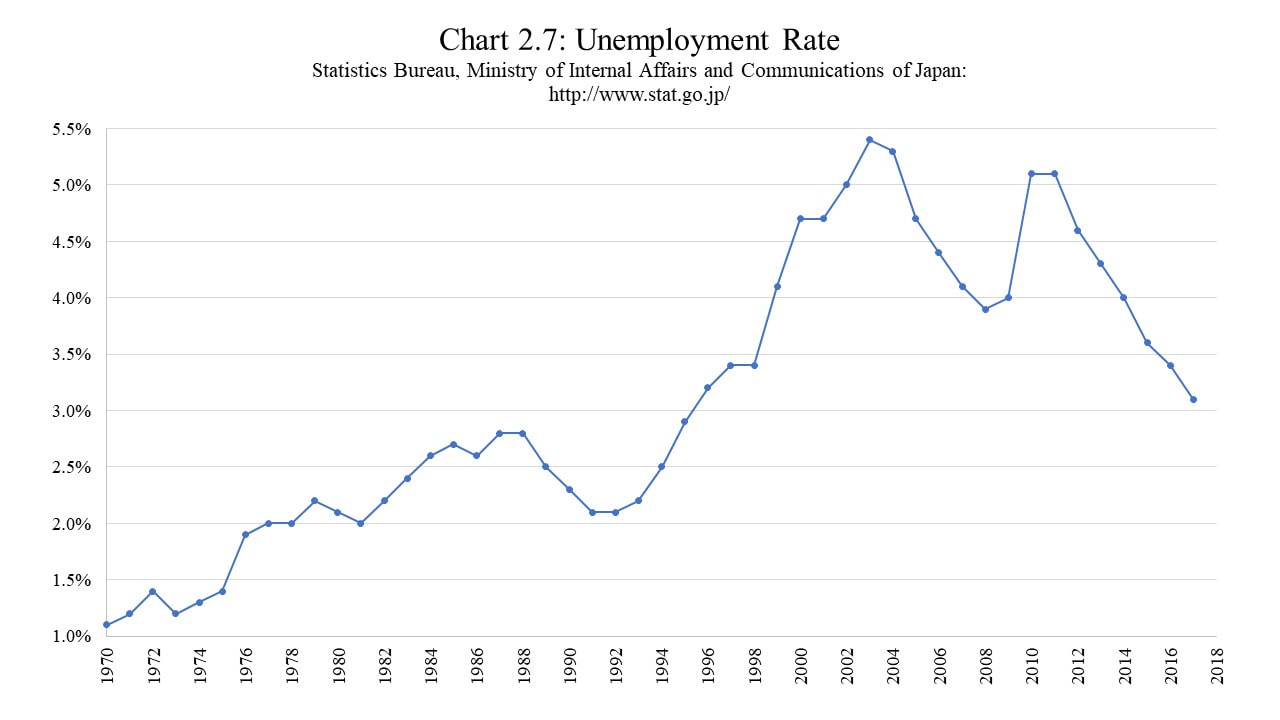

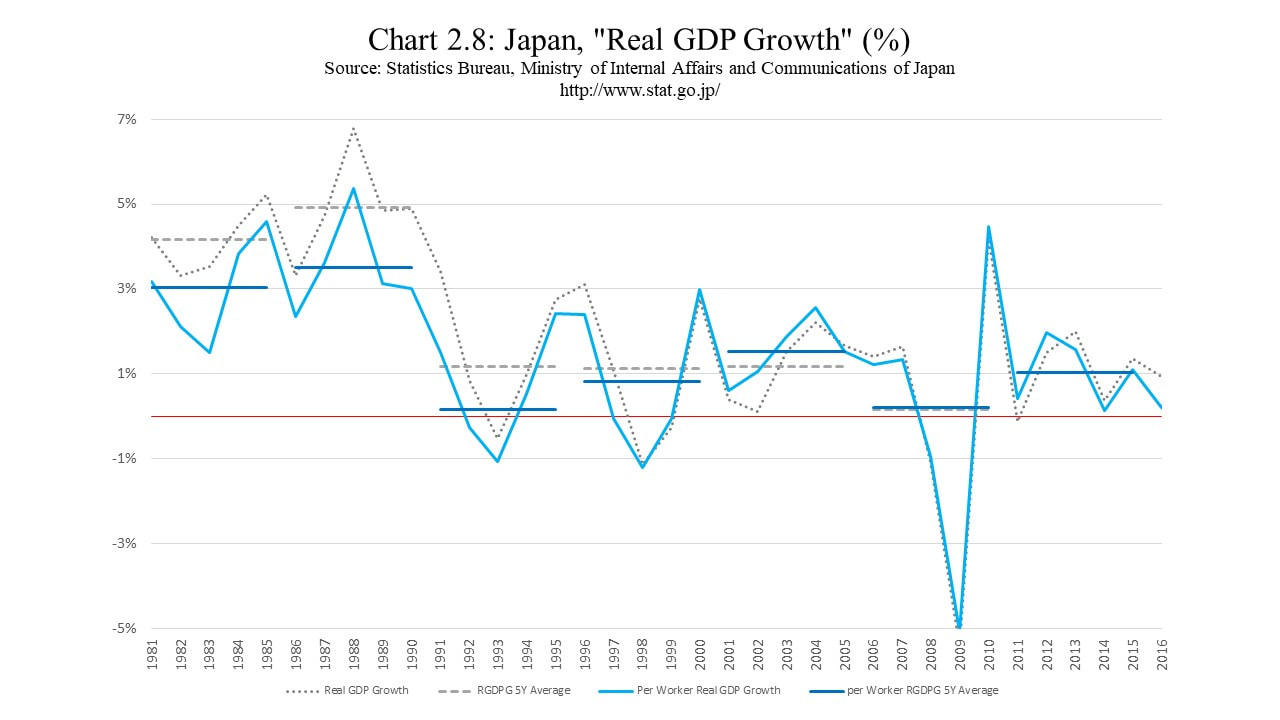

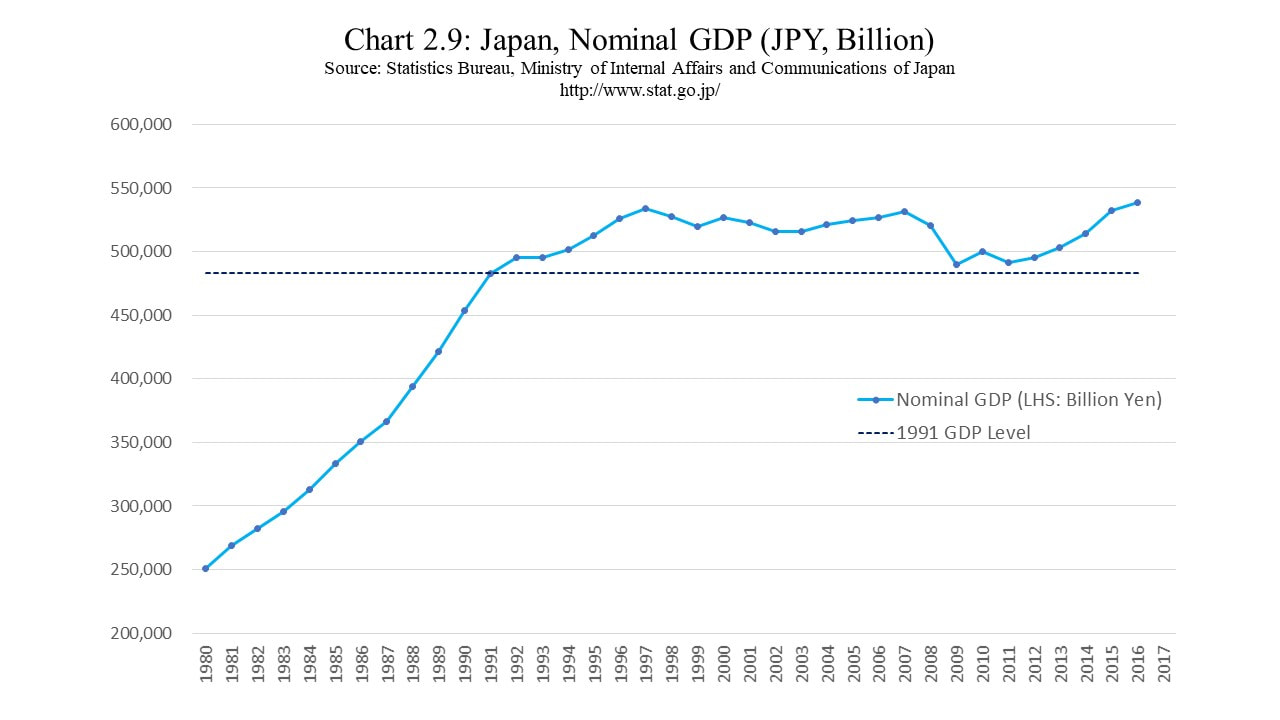

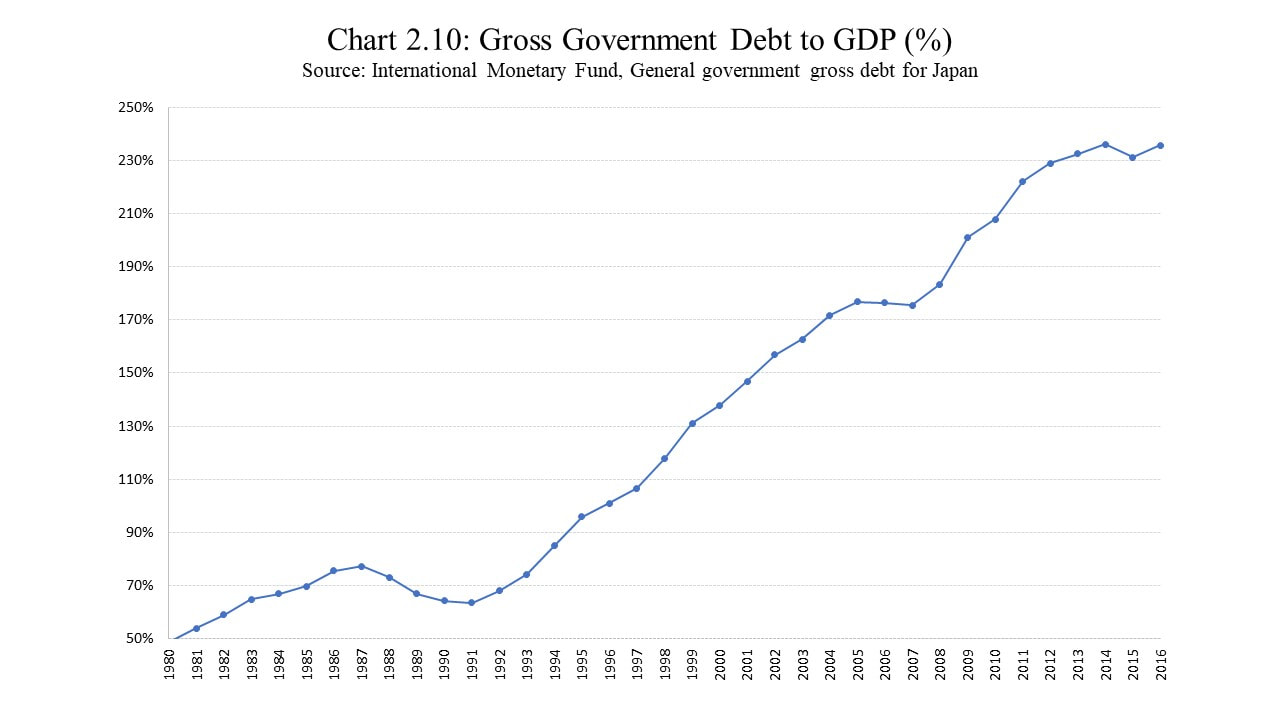

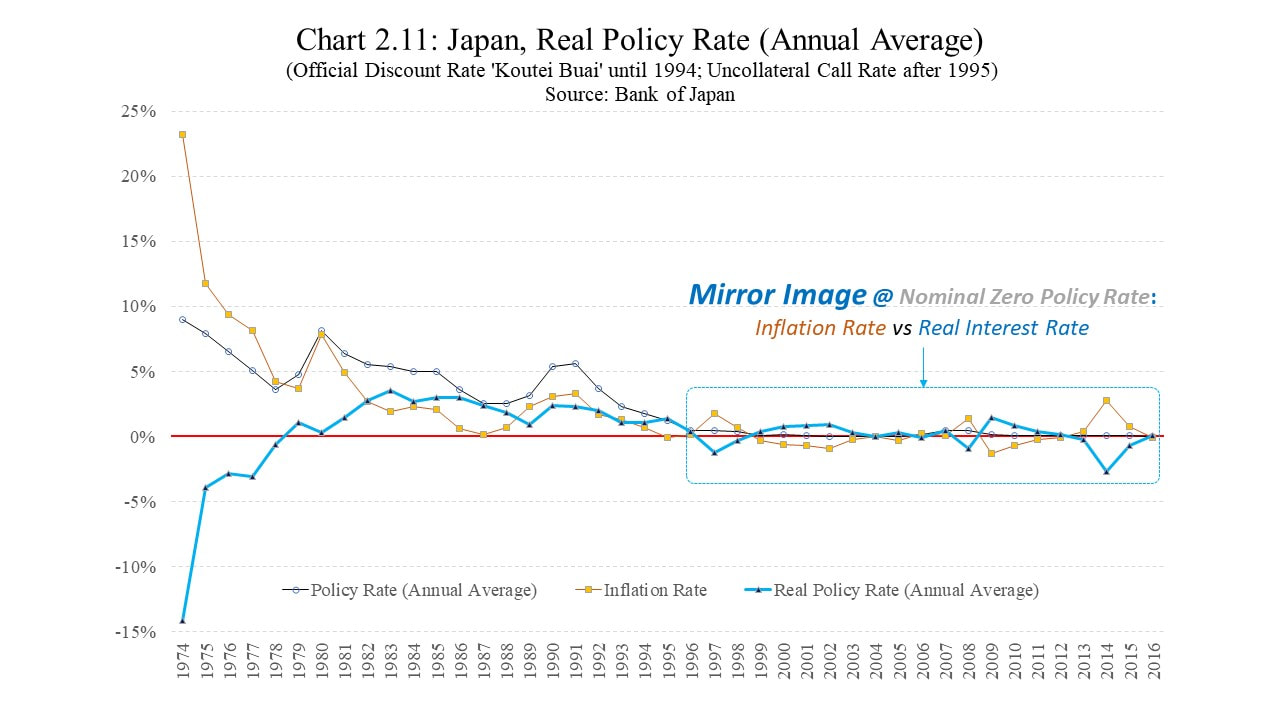

Part 1 of this reading compared two contrasting monetary wonderlands—deflationary Japan and inflationary Argentina—and illustrated how monetary conditions can shape our social, political, and economic behaviours. It also illuminated the interactive characteristic of the architecture of monetary wonderland: while a given set of monetary conditions shapes our particular collective behaviours, our monetary reality can also be shaped by our collective behaviours. In a way, our monetary reality, call it ‘Monetary Wonderland,' is a manifestation of a series of ‘feed-in and feed-back’ interactive dynamics between our collective behaviours and monetary reality. Part 1 also hinted a cyclical nature of ‘Monetary Wonderland.’ Every time a new economic imbalance emerged, it was a consequence of earlier developments that had arisen from another old economic imbalance. As an example, Japan’s ‘Lost Decades’ was a product of the preceding debt-driven asset bubble during the second half of the 80s. The collapse of the asset bubble ruptured the bubble time psychology as well as the bubble time economic reality. As a result, the post-bubble economic reality transformed into a protracted deflationary stagnation, called ‘Lost Decades.’ Furthermore, as presented later, the asset bubble itself was also an unintended consequence of its preceding events. In a way, our ‘Monetary Wonderland’ is a temporal manifestation of chain reactions in its past. In this passage, our monetary reality did not gravitate toward an equilibrium, but rather ran from one disequilibrium to another. With this cyclical notion in our mind, Part 2 goes a little deeper into the underlying mechanism of the cycle by examining how the cyclical nature manifested itself along Japan’s monetary experience since the 70s. Shirakawa’s Paradoxical Cycle of Monetary Policy:

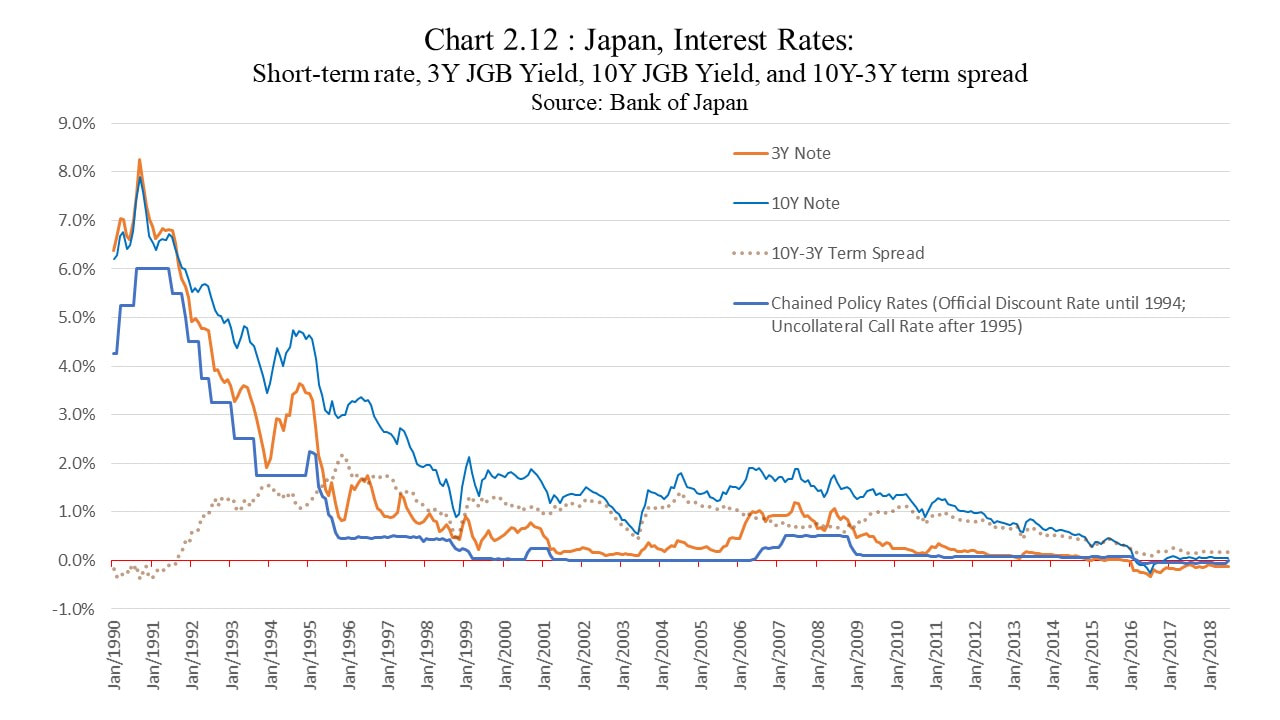

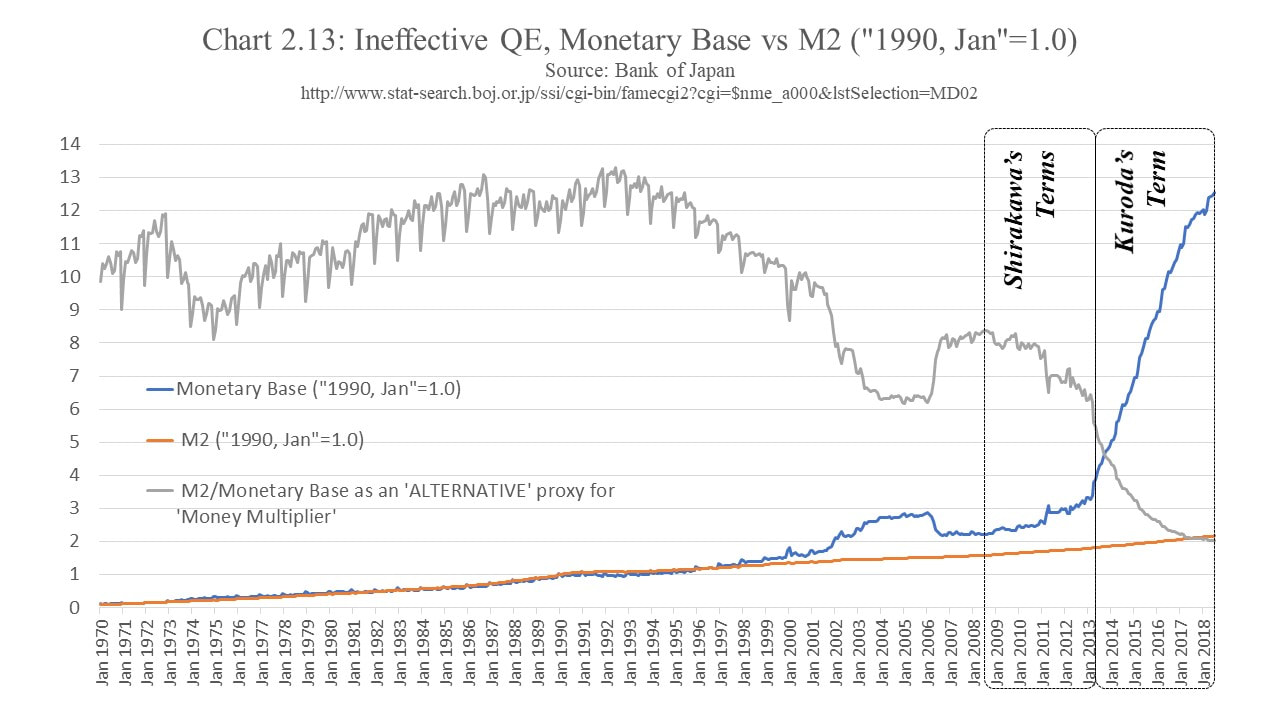

Masaaki Shirakawa, an ex-governor of the Bank of Japan from April 2008 to March 2013, expressed his insight of a paradox embedded in the conduct of monetary policy. Shirakawa illuminated how the success of monetary policy that had been aimed at economic stability paradoxically gave rise to unintended extreme economic imbalances and swung monetary reality from one extreme to another. Furthermore, he predicted that the conduct of conventional monetary policy could ultimately end up shaping an economic environment in which it becomes no longer effective. In Shirakawa’s perspective, the victory of monetary policy could defeat itself in the long run.

Now, I would like to integrate some other prominent economists’ insights into Shirakawa’s framework to illustrate the cyclical aspect of ‘Monetary Wonderland.’

|